Since 2013, a joint project between Costa Rican conservation authorities and wildcat NGO Panthera has worked to tackle the problem of jaguars and pumas preying on ranchers’ livestock.Over the years, it has introduced measures such as the installation of electric fences and the use of predator deterrence devices that have brought down predation numbers and also improved ranches’ productivity.The project’s information system has registered 507 reports of predation by jaguars, pumas and other wildcats, and offers crucial data to identify the main areas where these cats live and design intervention programs.With more than 400 farms participating in the project, it has proved effective in reducing economic loss caused by predation and improving the relationship between ranchers and conservation authorities.

See All Key Ideas

In February this year, a jaguar walked onto Wagner Durán’s family ranch, located near Tortuguero National Park in Costa Rica, and, in an unusual event, killed a calf. This area has the highest density of jaguars in Costa Rica, so it wasn’t unusual for that reason. What made it stand out was that it was the first time something like this had happened in seven years. But Durán says he doesn’t hold any grudges.

In the Lomas Azules community back then, every time a jaguar preyed on a cow it would mean up to $1,000 in losses for the rancher. The environmental authorities were treated as the enemy because they offered no solution, instead prohibiting the hunting of the big cats. “It was decided that you can’t touch the jaguar. What did that do? Make farmers angry and they’d kill the animal [even] faster,” Durán says.

His story is a common one among ranchers in the areas close to where jaguars (Panthera onca) and pumas (Puma concolor) hunt in Costa Rica. However, the situation took a turn with the arrival of a collaborative project between the wildcat conservation NGO Panthera and the Costa Rican environmental authorities. The Unit for the Attention for Conflicts with Felines (UACFel) is a pioneering initiative in Latin America, taking in reports of predation and working on solutions for those affected.

The initiative promotes peaceful coexistence between ranchers and wildcats through the implementation of advanced technologies and policies that have the added benefit of improving production on the ranches. Most importantly, they’ve reduced attacks significantly and transformed ranchers’ perceptions of the big cats.

In spite of the recent incident, Durán says that since 2018 he’s been able to see the benefits of jaguar conservation on his ranch firsthand. He’s now one of the most active cat defenders. In December 2023, he became a park ranger and helped three former hunters do the same. This transformation is an example of how improving data collection and carrying out interventions based on evidence in the communities benefit both humans and cats.

A puma in Patagonia. This species is an opportunist predator with great adaptability. Its progressive expansion north of Patagonia has been documented in different provinces in Argentina. Image courtesy of Franco Bucci/Rewilding Argentina.

Better information

Daniel Corrales is a biologist who grew up in a ranching family, and so has seen both sides of the conflict between conservation and ranching. Through his work with Panthera Costa Rica and the Project for Cat-Cattle Coexistence, Corrales has led a collaboration that has upended long-held perceptions and forged alliances with local ranchers to deal with attacks on their livestock.

His commitment helped formalize an agreement between Panthera and the Costa Rican Ministry of Environment that resulted in the creation of UACFel in 2013. This agreement allowed environmental conservation officers to get involved in data collection about predation on ranches. Initially, the information was collected manually, but in 2018 they started using an app that works even when offline and allows them to gather detailed data like the type of predator, coordinates, and photographic evidence of the attack.

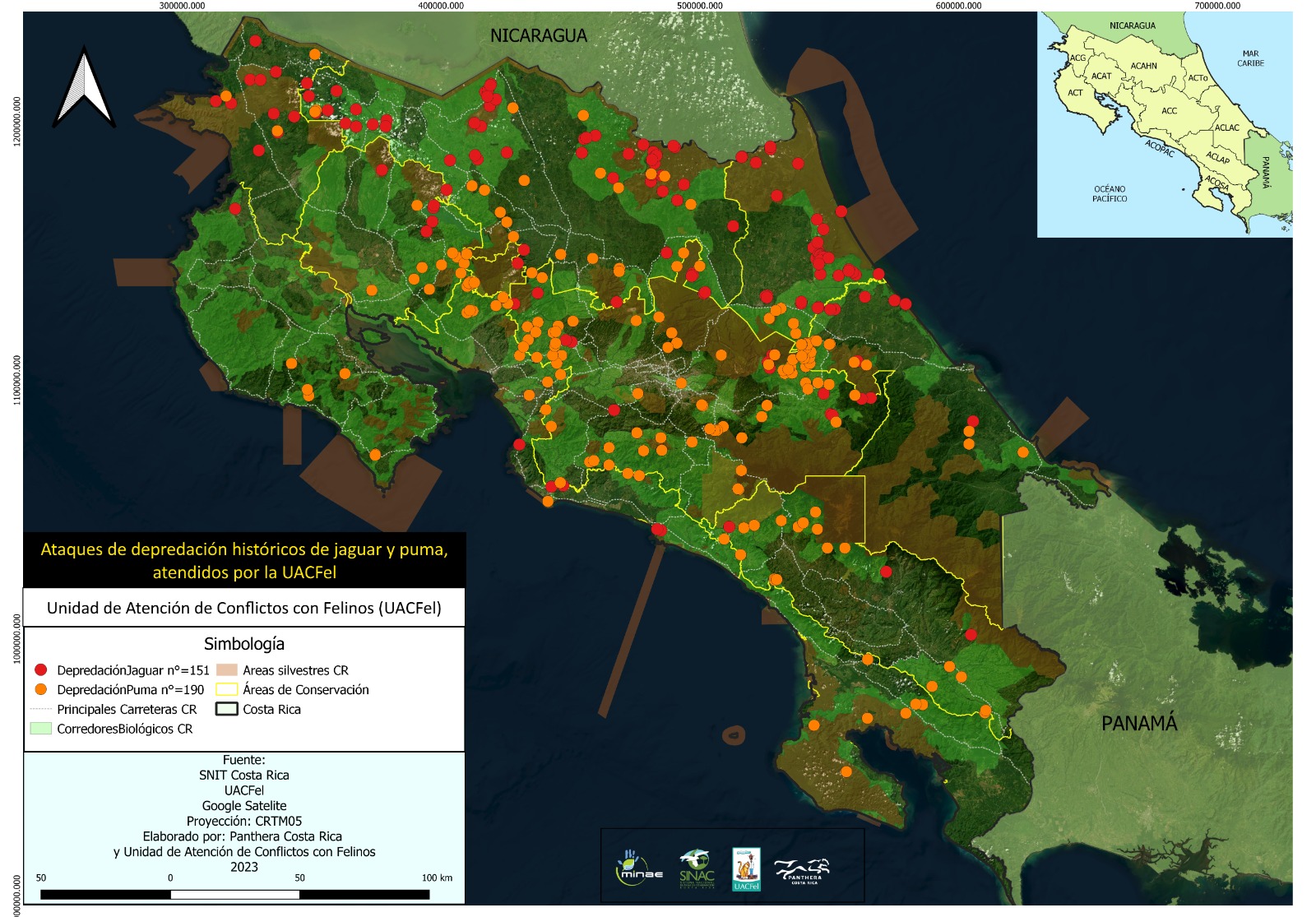

Between 2013 and July 2024, UACFel registered 507 predation reports, with pumas blamed for 201 attacks and jaguars for 156. Other species of wildcats native to Costa Rica, such as ocelots (Leopardus pardalis) and jaguarundis (Puma yagouaroundi), also prey on domesticated animals in rural areas, but their targets tend to be chickens and pets. Their attacks are also less frequent.

The information has helped create a map of predation hotspots that show most puma attacks occur along Costa Rica’s Pacific coast, while jaguars dominate in the north and the Atlantic coast.

This information has been essential to design programs with a specific focus. Although UACFel carries out interventions at the national level, its main areas of work are the farms surrounding Tortuguero National Park, Caño Negro Wildlife Refuge and Mixto Maquenque Wildlife Refuge. The latter is of special importance for jaguars’ cross-border forays, as it’s adjacent to Indio Maíz Wildlife Reserve in Nicaragua.

These areas stand out due to the recurring reports of jaguar predation. According to Corrales, although pumas are responsible of a higher number of attacks nationwide, their map of their attacks is larger and more scattered. In other words, the data indicate that pumas attack less frequently but in more locations.

Corrales says Costa Rica is one of the few countries in Latin America with a national network of biological corridors. The predation map that UACFel developed suggests these corridors actually work as intended, he adds.

Before UACFel was created, there were scattered efforts to address the conflict between ranchers and felines. The new initiative had to start from scratch because there hadn’t been any others like it with the same scope. The UACFel model has now been replicated in Panama, Colombia and Mexico.

Panthera says of the 35 countries in which it works, Costa Rica is the only one that knows, at a national level, exactly where predation attacks are concentrated and what species are responsible.

Corrales says he feels proud of a recent agreement with CORFOGA, the national cattle ranchers’ association that also promotes sustainable ranching. CORFOGA technicians also collect predation reports, which, according to Corrales, is a remarkable advance as ranchers tend to trust them more than they do conservation officials.

This collaboration hasn’t been easy to achieve. Corrales says UACFel worked for 10 years and presented evidence of successful interventions on ranches to gradually win the cooperation of ranching organizations. The data proved that the interventions not only achieved environmental conservation aims, but also led to greater profitability. “I always found it really unfair that, when there was a big cat attack, the negative feedback was always directed at us [the environmental sector] when there are institutions in the ranching sector that could improve conditions to reduce predation,” Corrales says.

After more than a decade of working directly with ranchers, he says, the experience has showed him that cattle predation means inadequate farmer management. His main goal is to change this reality.

Convincing ranchers not to kill cats

The proposals for more modern and productive farms also help conserve cats as they help ranchers to keep them at a distance.

Traditional ranches are usually vast expanses of pasture with one or two divisions. This enables overgrazing and soil compaction. UACFel has collaborated closely with farmers to install electric fences and water troughs, which allow for more divisions and intensive rotation of cattle. This approach, according to experts, improves the pasture’s health and keeps the herd in more compact groups, removing the need to find water in forest areas where the big cats can attack.

The project also promotes the adoption of water buffalos (Bubalus bubalis), a species that has evolved a defensive instinct against predators. These buffalos protect the convention cattle and have other attractive qualities: they’re hardier, meaning they’re more resistant to heat, need less veterinary attention, and graze on weeds that other cattle won’t touch.

Yet these measures still aren’t enough to keep the big cats away, which is why UACFel’s innovations go beyond improving the farms.

The main intervention is installing electric fences to prevent the wildcats from entering the pastures. This measure has been implemented at around 160 ranches, including that of José Luis Rodríguez, two hours outside the Costa Rican capital.

In 2016, the community here started experiencing puma attacks on dogs. Rodríguez recalls neighbors losing their pets, and even witnessed pumas taking them in plain daylight. At the time, he was starting a goat milk business, so his concern around potential attacks to his own animals increased.

After reporting the incidents to the environmental authorities, Rodríguez learned that his community lies within the Montes del Aguacate Biological Corridor. “For us, it was impressive to get to know that,” he says. “Pumas cross here, from the cloud forest to the dry forest, to exchange genes and strengthen the species.”

Rodriguez’s ranch was the first in the community to install an electric fence, serving as a prototype. He also implemented other deterrent devices to scare predators off.

Corrales is behind the development of devices like collars with bells and lights for the cattle, with the noise and flashing meant to deter would-be predators. He also came up with “antipredation posts” that emit light and high-frequency sounds activated by the movement of cattle at night. These techniques have reduced attacks to almost zero in the areas where they’ve been implemented, according to Corrales.

“The effectiveness of the interventions has been higher than 95%, and in cases where there has been predation, it’s been due to human error,” he says.

Since 2013, around $300,000 has been invested in improving more than 400 ranchers and in deterrence technology, financed mostly by international cooperation funds. The direct work with farmers and their communities has allowed Panthera to find funding in initiatives linked not only to conservation but to socioeconomic development. Although the final goal of the initiative is cat protection, Corrales says the interventions are carried out with and for the people.

“What we want is for the jaguar [mainly] to stop being the enemy and be the thing that drives progress, happiness, better management and more technology on the ranches,” he says.

A bigger balance

In the 1970s, Juan Ramón Durán arrived in Guácimo with ax in hand, intending to transform a piece of rainforest into a 50-hectare (124-acre) estate. But around 20 years ago, captivated by a new conservation spirit, he started reforesting the areas next to the gorges and he gave up hunting. He died five years ago, but his conservation spirit, as well as his ability to adapt and transform, passed on to his son Wagner, along with the ranch. For the younger Durán, being open to change has enabled his role as a pioneer in the collaboration with Panthera in his community since 2017.

The Lomas Azules community has seen the productivity of their pastures improve, and the ranchers have received training on topics related to cattle ranching in collaboration with UACFel. The biggest predation hotspot stopped suffering economic losses caused by cat attacks.

The positive results they observed on their ranches gradually opened up the Lomas Azules community to other conservation measures. A committee of volunteers came together to survey natural resources and take on challenges like poaching. “When we started, we identified 27 hunters,” Durán says, “and now there are only four left who are still causing trouble.”

Tortuguero National Park is renowned, and named after, the masses of green turtles (Chelonia mydas) that lay their eggs on its beaches. During nesting season, they’re a favored prey for jaguars. The rest of the year, jaguars are more likely to enter pastures in search of easy pickings. Durán says this is especially true for females looking for food for their cubs. Throughout his life, he’s heard of at least 40 jaguars being killed over predation incidents, and nine times out of 10 they were female.

It was also likely a female jaguar that visited his own ranch this past February and picked off a calf. His plot has 15 divisions, bounded by electric fences, and a year earlier he got water buffalos. Yet despite all these measures, there was still an attack.

Durán says “the stars aligned” in favor of the nighttime visitor. It was February, so no turtles nesting in the park, which made his ranch a more likely target. One of the main fences was broken and he’d forgotten to check it. In addition, he’d separated the buffalos from the rest of the cattle and hadn’t put them back together. Durán speaks firmly and without a trace of resentment when he apportions blame for the incident: “It has been seven years and I’ve only had this incident with a jaguar. It was my fault.”

Banner image: A jaguar photographed by a camera trap on a ranch with predation issues in La Amistad Caribe Conservation Area in 2014. Image courtesy of Panthera Costa Rica.

This story was reported by Mongabay’s Latam team and first published here on our Latam site on Aug. 1, 2024.

Author :

Publish date : 2024-10-03 12:45:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.

—-

Author : theamericannews

Publish date : 2024-10-04 09:48:14

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.